In professional and home studios around the world, Radial’s Reamp® units have become synonymous with performance, innovation, and rugged reliability. And while Radial continues to innovate the process of reamping, as exhibited in its latest product, the Reamp® Station, reamping had its humble beginnings starting with San Francisco-based engineer and producer John Cuniberti.

John’s first homemade Reamp® box design became so popular based on word of mouth that he wasn’t able to keep up with the demand by artists such as Eddie Van Halen, Joe Satriani, Prince, and others. Radial approached John about acquiring the assets of his company and in 2011, John sold his design and the assets of his company to Radial, and the rest, as they say, is history.

In this interview, we talk to John about the early days of his Reamp® business and how it took off. You can find out more about John on his website at johncuniberti.com.

Radial: Let’s start by rewinding back to the 80s. You’re in the studio and are looking for a way to feed a guitar amplifier with a pre-recorded guitar track from a two inch Studer tape recorder. What were the circumstances around that?

John: I had recorded a live album for Joe Satriani in New York and it was done in the traditional way — with a remote truck parked outside the venue. We recorded a direct signal from the bass via a direct box. And another track with the microphone on the bass amp itself.

Radial: So the beginning of the Reamp® era started with bass, not guitar?

John: Yes, apparently, sometime between soundcheck and the live show, the microphone feed coming from the bass amp developed a buzz. I ended up with a pretty nasty buzz on the bass guitar amplifier on the recording.

Radial: What about the direct out from the bass?

John: The direct out from the bass was clean, but the amplifier itself was problematic throughout the show. They tried to fix it during the show, but it was one of those nasty 60 cycle hums coming out of the rig.

Radial: Were you aware of it at the time?

John: No, I wasn’t. Remote trucks are noisy inside and I was likely just listening to both the mic and amp. So, when it came time to mix the record in San Francisco, I push up the fader for the bass amp, and there it is — that annoying buzz.

Radial: But the performance was fine and intact?

John: Yes, the bass performance was great except for the buzz. So, I pushed up the DI track and it was clean like a DI track should be. So once we started mixing, I said, “Well, I’ll just use the direct feed track.”

Radial: So, problem solved, theoretically!

John: Yes. So we started mixing and, I don’t know, we just weren’t feeling it. And I just kept thinking, “I think one of the problems is that we don’t have an amplified bass. We don’t have any ‘growl.’ It doesn’t sound like a live record. It sounds too much like a studio record. The bottom end is just too clean. I think we really need to dirty this thing up.”

Radial: So you started looking for a solution.

John: Yes, remember … this is the early ’90s, pre-digital. We didn’t have any real method for dirtying up a bass that’s been cut as a DI. So Joe said to me, “Well, why don’t we just take the DI, stick it into a guitar amplifier, put a microphone on it, dirty it up and record it?” I said, “Well, there’s going to be some problems with that because of impedances.”

Radial: Had you tried this before?

John: We had in the past when we’re trying to do special effects and stuff, which was to take a passive DI and invert it. In other words, take the output of the direct and plug a tape recorder’s output into it, and then take what would normally be the input of the DI, and plug it into the guitar amplifier’s input. In other words, it’s a reverse DI.

Radial: Did that work?

John: Well, it has to be a passive box to do that. Because effectively what you’ve done is dropped the level down a bit, but the impedance is not correct. And the transformer really doesn’t like it. And so you don’t get a flat response and you can pick up a lot of distortion.

Radial: So did that work?

John: It wasn’t perfect, but we went ahead and did that, and I kept thinking as we were mixing this record, “There’s got to be a better way. This just doesn’t make any sense.” So I began thinking, “Why hasn’t anybody made a box that sends the signal the other way — plus four line-level professional recording equipment, whether it be a tape recorder, or a recording console, or a piece of outboard gear — with the ability to adjust the impedance and gain and inject it into a guitar amplifier in such a way that the guitar amplifier thinks the guitar is plugged into it?

Radial: So this was kind of the a-ha moment?

John: I just thought, “Somebody needs to do that.” And so I went to the studio’s tech who is a friend of mine. He had his own office in the studio filled with a lot of test equipment. And I told him what I was trying to do and said, “Can you do this for me?” And he says, “I can’t see why that would be a problem.” He pulled out this big cardboard box that had a bunch of transformers in it and he rifled through it and he pulled out this huge, big UTC transformer. And he says, “I think this might do it. It has the right input and output impedance, and we could get the gain down. We just need to put the right connectors on it.” And I said, “Well, can you put that thing in a metal box and bring it to me? I’m downstairs mixing this record.” So about an hour later, he shows up and he’s just got this huge transformer stuck in a metal box, drilled a couple of holes, put an XLR on one end and a quarter inch female jack on the other, and hands it to me. And I go out to the studio and plug it in, and it sounded 10 times better!

Radial: This is still for the bass track on the Joe Satriani record, correct?

John: Yes. Joe walks in and says, “What are you doing?” I said, “Check this out. It’s like Stu is standing here playing.” By then we had this big SVT bass amp in the studio. And I had that makeshift Reamp® box plugged in and turned way up like it would be at a concert and it was amazing! I threw a microphone on the cabinet. And we went into the control room, pushed up the bass amp fader, and there it was. It was exactly what it needed!

Radial: Did you do this for any other songs?

John: Yes, we continued mixing that song, and then I went back and remixed three others using the makeshift box. Obviously there was no automation in that day, so we had to go back and remix. So we lost a day or two of studio time, but the sound of the bass was correct. It sounded like it was supposed to sound.

Radial: So the genesis of the Reamp® box was not for a guitar track, but for a bass track.

John: Yes, that’s correct! The Satriani record was the impetus for why that box, the original prototype was built.

Radial: What did you do with the prototype from there?

John: I didn’t have a name for it or anything. I carried it around with me for other sessions, trying to think of ways of how I might be able to use it. At that time, I wouldn’t say I didn’t take it seriously, but I was really busy being a recording engineer and a record producer. I really wasn’t into building and manufacturing stuff.

Radial: What was going through your mind? Were you starting to think at that point about turning this prototype into a real thing, or was it going to be a quirky little box that you carried around? At what point did you start thinking about maybe this is going to become a real product?

John: There is a guy by the name of Stephen Jarvis that still lives here in the Bay Area. And he was the go-to equipment rental house in San Francisco. All throughout the ’90s he had a warehouse filled with all the latest and greatest audio gear, black boxes, Dolby racks, microphones. And when you came in, whether you were from out of town, or just a local guy, and you wanted a U47, or the new AMS reverb, you’d go to Stephen, and he would bring it to the studio and plug it in for you. He was making a fortune on rentals, and he was great.

Radial: What role did he play?

John: We were renting a bunch of gear from him. I think he saw the prototype box when he was in the studio one day and I probably even told him about it. I didn’t think much of it. A couple of months go by and he sends me a letter with a check for 500 bucks, and says, “This is a down payment for two of your interface boxes because I think I can rent them.” And I went, “Oh, huh!” I hadn’t even thought of that. Then it occurred to me that maybe somebody else might want to do what I did with it. So I built three more boxes, and I gave him two, and I kept one. These were built better, with better connections. They weren’t just a cheesy little prototype. It was actually more refined, something that remotely looked professional.

Radial: Did you have a name for it at this time?

John: I was kicking that around, thinking, “I’ve got to name this thing something.” So I said, “I’m going to name it the Morning After Box, so if somebody loves their performance but not the sound, they can come back the next day and re-amp it, and it’s all good.” But I got talked out of that, which is probably good. So I finally came up with the idea of calling it what it actually does, re-amp. So I decided on the name Re-amp. I got some rub-on letters and put letters on the side of the box and I called it a Re-amp. I gave it to Stephen. He rents it to Mark Needham, Eric Valentine, and a couple of other local guys. And people start calling me and saying, “Hey, I want to own one. Can you build me one?” And so the demands for these things started coming in and I thought, “Wow, I’m actually going to get in the manufacturing business.”

Radial: How did you go about that?

John: I decided that I would test the waters and build 50, but I had to redesign it completely because the boxes I had didn’t look professional enough. And that big UTC transformer was rare and very, very expensive. So I got a smaller transformer by UTC called an 0-10. And we designed a new circuit for it on a PCB. And then I thought, “Well, what kind of box can I put it in?” So I went and got tubing, 20 feet of this aluminum tubing and I cut it. And then I had the chassis bent and I slid those things in. And I tied them together with a screw on the bottom. I had them all anodized, and they were called Re-amp and they cost me over $100 apiece to build, and I built 50 of them.

Radial: So all of a sudden, you were in business!

John: I had boxes of them in my garage. I remember standing there looking at them going, “What did I do? This is insane. What a waste of money. Nobody is ever going to want to do this. Why did I get talked into this? I built 50, so I could sell three or four to some friends of mine who are engineers.” That didn’t make any sense. I sold three, I sold four, and then I sold 10, and then four or five weeks goes by I sell two more. Then I thought, “You know what? Since Stephen’s rental company is introducing these things to people and that’s how this whole thing got started, I should just send these things to rental companies in L.A.”

Radial: Up till then it had been limited to the Bay area?

John: Yes, very limited availability. So I put together a little letter explaining what the Re-amp is, and how people that the rental companies rent gear to might be interested in using it. So I sent these LA rental houses the letter with the Re-amp for free. It was $100 in advertising. So I just sent it to all these rental companies in L.A. that were hugely famous. I sold the 50 Reamps probably within two months after that. The word just got out.

Radial: Did demand pick up in other cities?

John: Yes it came from all over because these engineers that were working in L.A. heard about it and used it, but they were from New York. I was getting requests from people from all over the country for these. So I thought, “Well, I guess I’m in the Re-amp business.”

Radial: And so were you doing all this yourself at this time, or did you have some help?

John: Mostly myself. I had a local metal work company cut the chassis and finish them, and then bend the chassis and drill the holes. Then I had a buddy from one of the studios come over and we’d spend a Saturday and a Sunday in my backyard wiring these things up. And we could probably do 10, 15, 20 of them in one day. I got all the parts, laid them all out in front of us, and we just built them there in the backyard. I also had a company do all the anodizing, and the screen printing. And then we would assemble them. And then I would wrap them up in bubble wrap, put them in a box with just one piece of paper to explain what it was and how it worked. And that was it, and then I’d just waited for orders.

Radial: How were you handling the sales process?

John: Remember, this is before the internet. So I would get phone calls, or letters from people. In fact, I got a letter from Edward Van Halen. “I heard about your box. I want your box. Here’s a check. Send me your box.” Like that. And so I would wrap these things up and I would ship them and I’d make 50. And then I made another 50, and then maybe a year later I decided to maybe do a run of 100. And by then I got away from anodizing and I started having them powder-coated. And when I started powder coating, I could do different colors. So I decided every year I would do a different run of color.

Radial: What was the color of the first run?

John: I think my first run might have been black. My next run was Neve gray. I did red ones later. So, I would change colors. And then this guy that worked for Prince called me and said, “Hey, Prince wants a couple of your Re-amps.” And I thought, “Oh, man, I’m just about to do a new run. I think I’m going to make some purple ones.” So I did a run of about 10 or 20 purple Reamps. And I sent two to Prince and I called it the Prince issue.

Radial: Did it actually have a product name at this time, or were you just calling it the Re-amp?

John: I decided that I better get a trademark for the name, so I applied for a trademark for Re-amp, and the trademark folks got back to me and said, “We can’t do it.” Turns out there was some other product by a company called Re-amp, and it had absolutely nothing to do with music, or guitars, or recording or anything. But the trademark office said, “They already have Re-amp — with the hyphen — and it may be confusing.” So I said, “Well, what if I take the hyphen out of it?” And they said, “You can do that.”

Radial: So that solved the trademark issue?

John: Yes, when they told me that, I said, “Okay. I don’t even know why I had to put that in there.” So I took the hyphen out and then I went back to the Letraset store and I went through all these different fonts that they had. And I found the same one that Radial is still using today. I laid it out, and that was the one I started using.

Radial: So you got the trademark, what about a patent?

John: At the same time I applied for the trademark, I also applied for a patent for the Reamp®. John LaGrue of Millennia Media recommended that. He said, “If you really want to start selling these things and get into this business, you may want to get a patent for it.” And I said, “A patent, that’s expensive. They’re not going to give me a patent for this. Somebody must have already thought of this.” And he goes, “No, I don’t think so.” So I went to the patent library in Palo Alto and I spent two days going through everything that would have been considered what they call prior art, which is electronic circuits that converted plus four line-level to minus 50 guitar pickup level. And, again, this is before the internet, before computers. So it was a painstaking process.

Radial: What did you discover in the research?

John: I went through everything and I went back to John and said, “Man, you know what? I may be able to do this. Nobody’s really bothered with it.” Because think about it. I worked in studios that had echo chambers, which were speaker cabinets powered by amplifiers in rooms being fed from the control room at plus four line-level, microphones in the room picking up that cabinet, and then rerecording the sound as reverb. So I thought, “Well, that’s all I’m really doing. How can I get a patent for that?”

Radial: So what did you do from there once you found this out?

John: I had to get a patent attorney. It turns out that if you write a very, very descriptive document on the application part of it, for example how it’s going to be used, you can pull it off. So, if it’s a box with a transformer and a couple of jacks in a small, simple circuit, they’re not going to give me a patent for that because the transformer is doing exactly what it’s supposed to do — transform. So the idea about how the transformer is going to be applied in a setting was patentable.

Radial: Did you still have doubts about the patent-ability of the box?

John: Yes, but John LaGrue said, “Listen, once you apply for your patent, you can put “patent pending” on your box. And if you put patent pending on your box, you’re probably going to keep away a whole lot of people that might try to challenge it. And I went ahead and did it. I think I applied for the patent in ’95, which was only two years after my first prototype. I didn’t receive the patent until December of ’99. I got this letter in the mail from the patent office and I went, “Oh, I completely forgot about this.” It was three years later.

Radial: Were you still making and selling boxes in that period from ’95 to ’99?

John: Oh, absolutely. I continued to make the boxes up until 2011.

Radial: Were you still making them by hand, or had you gotten into any kind of manufacturing automation?

John: A guy with an audio electronics distribution company in Maine reached out to me and asked if I would be interested in them distributing the Reamp® box. And I said, “Yeah, but I can’t deal with the numbers right now. I can’t build them fast enough.” And he goes, “No worries. We’ve got a guy in Indiana that can build them.”

Radial: So you would hand the manufacturing off to someone else.

John: Yes, and my first thought was, “Oh, man, this is going to get sketchy. I can’t control the quality. Everybody’s going to want a piece of the action, and I’m going to end up with nothing.” So I really gave it a lot of thought and I think I signed an exclusive rights deal with them for one year.

Radial: How did that work out?

John: After a year I realized that these guys were taking way too much off the top and not really doing their job when it came to promoting and advertising. I was personally running ads in all the pro-audio magazines, EQ, Mix, Tape Op. They really weren’t doing that much. So after one year I cut them loose, but I maintained the relationship with the manufacturer and continued to have these guys build the Reamps for me.

Radial: DId they make any improvements?

John: Yes, I went with a custom transformer. They were also powder-coating them.

Radial: What happened to your main job as a recording engineer/producer during all of this?

John: Well, because I wasn’t making them by hand anymore, it became super easy for me. The manufacturers would just send me the finished boxes and I would package them individually, stick a label on it and I would ship it. So on my way to the studio every day, I would just go by the UPS office and drop off three or four or five Reamps. It was pretty straightforward, and pretty easy for me to do that.

Radial: How many were you producing at this time?

John: It was still expensive because I had to put up a lot of upfront money to get the numbers down. I think the most I ever made at one time was maybe 250 of them. I got the price of manufacturing down where I was selling them for a profit. But I was still paying for all the advertising and marketing.

Radial: You mentioned Eddie van Halen earlier. Did he ever end up using it and tell you about it? What guitar players at that time did you start hearing from and knowing that they were using it?

John: With the exception of a couple of guys like Steve Vai, and, of course, Satriani, I was never in direct contact with any of the players. Most of the time the Reamps were being purchased by their people. For instance, Metallica bought a couple, but it wasn’t James that called me up. It was somebody that works in production that bought that. I know the guys from Green Day bought one. Also Beck, the Rolling Stones.

Radial: Did engineers also show interest in the Reamp®?

John: Yes, definitely a lot of engineers had these things. Jack Joseph Puig used them. Andy Johns loved it. Like I said, Steve Vai used them. They were out there and being sold. I would get invoices from companies, but I didn’t know who they were.

Radial: Were you still sending out free units to create awareness?

John: Yes, besides sending to rental companies, I just sent them to recording studios with a letter saying, “Here. This is what it does. Your engineers might be interested in it.” I got a letter back from Allen Sides from Ocean Way. He sends me the Reamp® back and says, “I recorded it right the first time.” 10 years later, once Reamp® had become a thing, I ran into him at the AES Show. He puts his arm around me, and says, “Hey, man, can I get that Reamp® back?”

Radial: Any other bands besides the Stones, Green Day, Metallica?

John: I know Aerosmith was using them. Dave Matthews had one.

Radial: So it was really an organic process of marketing the boxes in the beginning.

John: Yes, putting them into the hands of people that were going to use them was the best advertising I could possibly ever do. I couldn’t have paid for the kind of exposure Sylvia Massy was creating for me. It just made sense. And then I started hearing that people were doing things with these Reamps that I never had intended, or ever ever imagined. Such as re-amping a snare drum, re-amping vocals through guitar amps, or foot pedals.

Radial: The use of foot pedals for reamping has become really popular.

John: Yes, I never thought about that. The guys out there were doing it. They were going, “I never Reamp® anything, but I run the shit through my foot pedals.” And I’d say, “Oh, I never thought about putting a vocal through a wah-wah before, but now you can. That’s awesome. I had never thought of that.”

Radial: So the whole creative side of reamping began to come out.

John: Yes, I think that, and the home studio really is what made it happen.

Radial: Why the home studio as opposed to the professional studio?

John: Because I didn’t have an audience of 100 really great recording engineers that can afford 200 bucks. With the home studio market growing, I could target anybody who goes to a guitar center and buys a recording setup, comes home, and calls himself a recording engineer. Now I’ve potentially got thousands of customers.

Radial: And they were avid buyers of gear.

John: And they all read music magazines. They’d all want the little $200 box that Beck, and the Stones, and Van Halen, and Andy Johns used. Everybody wanted one, but that created another problem. I began getting phone calls,letters, emails saying, “Hey man, my Reamp® doesn’t work. What’s wrong with it? I need to send it back because it’s not working.” And it’s like any qualified engineer that knows anything about anything could figure out what a Reamp® does in about 12 seconds. Plus four line- level, balance in, guitar level, unbalanced out. I started getting Reamps back that were blown up because the buyer thought they were speaker soakers or direct boxes with the wrong connectors on it.

Radial: People were blowing them because they didn’t understand how to use them?

John: Yes, It started off with I would get maybe one or two returns, and weird emails, letters a year. By 2011 when I handed it off to Radial, once a week somebody complained that the Reamp® didn’t work because basically they didn’t know what it was, and they didn’t know how to use it.

Radial: Was this part of the blessing and curse cycle of the home studio? A larger audience of buyers, but buyers that may not have been as educated on the equipment?

John: In every case. From ’94 when I started packaging and building Reamps up until I sold to Radial. I think I only repaired maybe two Reamps the entire time. Only two were sent back to me, and it was only because the transformer came off the PC board when it got dropped, or something. I would never have to explain to Mark Needham or Bob Rock how to use a Reamp®.

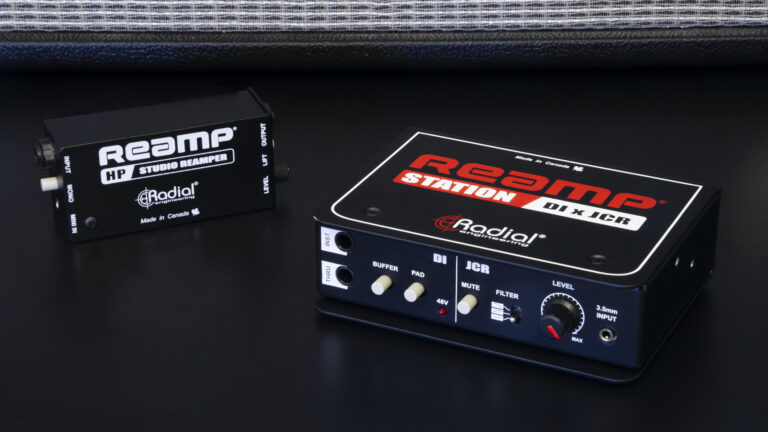

Radial: Let’s fast forward to the present day and Radial’s introduction of the Reamp® Station. I understand this unit is similar to what you originally envisioned when you built your first Reamp® box, true?

John: Remember the story about the tech who went through the box and he found that big UTC transformer? At that time he said, “Oh, by the way, this would make a great DI, also.” So my very first prototype was both a DI and a Reamp®, and I still use it because it’s a fantastic direct box. I still use it as a direct box, but when I decided to go into business to make Reamps, I didn’t want to include a DI for a couple reasons.

Radial: What were the reasons?

John: First, it was going to cost me too much to have a multifunctional transformer that was going to do both things well. And everybody has their favorite DI so why would I want to get into that business? And it was just going to be heavier, so shipping was going to be more. I just exited the DI business right away. I didn’t want to compete with other people’s idea of what a good DI sounds like. That’s a whole other world.

Radial: So you think it benefitted from being a sort of specialty box?

John: yes, it probably benefited from the fact that it was really a specialist piece of equipment, if you will. Think about it … would Eddie van Halen or Joe Satriani have taken as much interest in it if they had heard that it had a DI in it? They were probably more likely thinking, “Now this does one thing really good. I just want something that does one thing really good.” And maybe that was a benefit early on.

Radial: Before we finish, talk a little bit about what you’re doing these days.

John: Well, I’m primarily a mastering engineer. I opened my own room at The Plant in Sausalito in 2000. And I was there until 2008 as the chief mastering engineer. And then when the entire studio closed, I moved it to my home and I’ve built a room and I’ve been happy as a clam here mastering records all day. So that’s my primary thing, but I also mix and do recording sessions for other people.

Radial: Do you still work with Joe Satriani?

John: Yes, I maintain my relationship with him and I still do records with him. In fact, right now we’re taking a close look at remixing some of his classic records for ATMOS.

Radial: Talk about the OneMic Series on YouTube.

John: Yes, it is a series of 30 videos that demonstrate how you can record an entire band around one stereo microphone. Everything is videoed, so you can see the entire process. It’s called OneMic: The minimalist recording series.

Radial: What do you do on the videos?

John: Basically I take a band — electric guitars, drums, everything. I get them around one stereo ribbon microphone in a nice room, and I spend a lot of time balancing the singers against the instruments and then apply some mastering techniques. I’m basically trying to recreate a multi-track, multi-channel recording with just one stereo microphone in the room.

Radial: Thanks for your time John!

John: My pleasure!